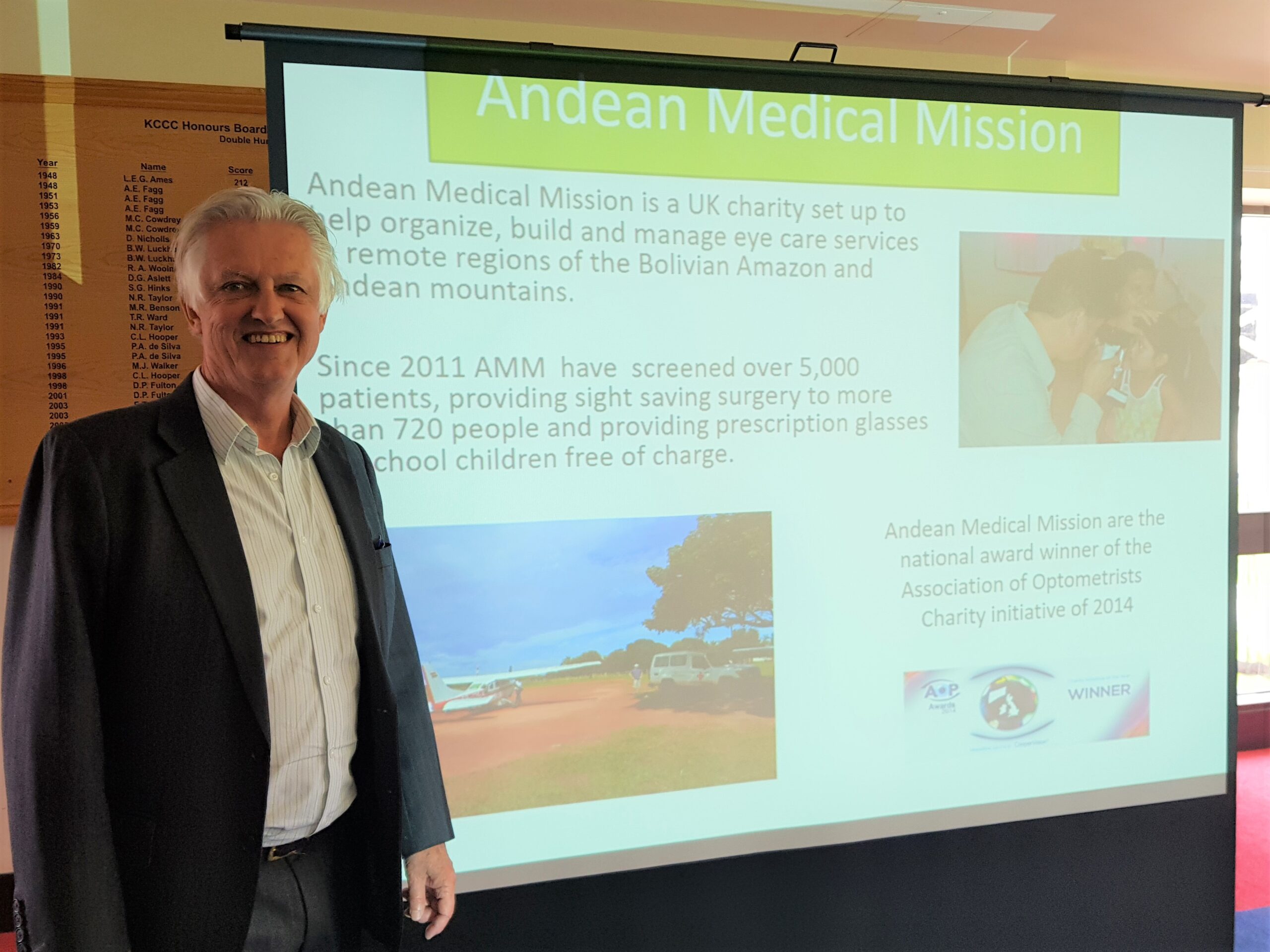

Some time ago our Club gave a donation to Romain towards travel to Bolivia for the charity that he volunteers for, the Andean Medical Mission (AMM). But when handing over our donation we certainly underestimated the challenges that Romain and others would face in their task!

Romain is Belgian but lives local to Canterbury and has children educated at nearby schools. AMM aims to help improve eye healthcare. Its strategy is mainly one of prevention and treatment – for instance, through screening for treatable diseases and educating families, schoolchildren and healthcare professionals about eye health. The aim of Romain’s trip was to train local doctors in specialist ophthalmic skills and also to help carry out eye surgery.

Bolivia is a landlocked country that borders Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, Chile and Peru; it’s divided from the latter two by the magnificent Andean Mountains. The capital is Sucre while the seat of government is located in La Paz.

Bolivia seems to be a land of superlatives. La Paz is the highest capital in the world and lies not far from Lake Titicaca, the largest lake in South America and the highest lake anywhere. Mount Illimani, one of the highest mountains in South America, can be seen from the city. Bolivia itself, with a population of over 11 million, is one of the poorest countries in South America. There is a high level of visual disability and blindness – and a big disparity in need. Unfortunately it is the poorest, most remote regions that need greatest help – but these are the hardest to help because of poor infrastructure and a lack of medical personnel. There are also other challenges – which Romain soon found out.

The plan was to travel to two rural villages – the village of Baures near Santa Cruz and a tiny village called Remanso, near Brazil. Romain would work as part of a team, later meeting up with David Goldsmith (the doctor that set up AMM) who, using magnifiers and eyecharts, had already screened for potential “treatable” patients.

Romain’s journey kicked off with an 11 hour flight from Madrid to Santa Cruz airport where he met with colleagues. From there the team had an hour long taxi drive out of the metropolis to a small airfield (“practically a grass landing strip”) where they boarded a small aircraft for the onward journey. The plane was disturbing at first sight thanks to appearing to have back-to-front engines; in fact it was one of a series of only four planes specially developed to take off/land in restricted areas.

The weather was very bad, so the team had to wait for 4 hours for it to clear and start their 2 hour journey to Baures. But, just an hour into the flight, the weather deteriorated so rapidly that alternative airports (needed for such flights) closed down due to lightning. This meant flying became unsafe, so the pilot decided to land on a ranch “on the way”. Visibility was extremely poor; nevertheless the pilot managed to touch down – but with one side of the plane dipping as this was marshland! He had to take dramatic action to stop safely.

Having breathed a collective sigh of relief the team un-boarded and went to the ranch. They stayed there, waiting for the weather to clear up. It was time for exploration of the ranch, with piglets running around and impressive agricultural machinery on site for farming soya and sugar cane. Mosquitoes were a pain – and a disease carrying risk at both night (chikungunya) and day (dengue). There were also a number of snakes, some of which were venomous.

Finally, after 3 days, the weather improved. The pilot flew the plane a short flight away from the ranch by himself and the rest joined him by car to fly on together to Baures.

The team were very well received in Baures, the “Chocolate capital of Bolivia”. They were met by David Goldsmith, and thanks to good community feeling a number of locals had volunteered to help their work. While driving through Baures the team spotted the local “cathedral” – not quite like Canterbury’s. It was the size of a small church but of huge cultural value because of its Indian history.

The team faced further clouds and torrential rain in the afternoon…and then encountered “a plague” of beetles and ants which just “flew around and suddenly died!” (In the field operating theatre the role of one nurse was mainly to swat away bugs!)

The surgical room was disorganised, meaning lots of time was spent looking for items before operations could even start. Equipment (e.g. the operating microscope) was basic, lighting was rudimentary and the surgical chair not adjustable (basically it was a stool on blocks). But a big plus for the team was that the operating room had air conditioning, which was important given the extremely humid conditions.

The team set to work on patients – seeing 35 in all. One of the first cases had a pterygium – a benign, noncancerous growth (common in high exposure to UV) growing over the cornea (the clear front covering of the eye) that in extreme cases can cause sight loss. Its removal is easy but it needs a transplant of healthy tissue so takes time. Romain also removed cataracts – some so advanced the lens had turned amber-brown. One patient had a lipoma (lump of fat) removed from the eye. They also got a call about a young girl 200 km away that had hurt her eye when she ran into something. She was brought to them. Luckily there was no penetration or perforation – just a lot of plant material in the eye that had to be cleared. It was a lot of effort and expense for something relatively simple – but of course there was no one else around her to help, and without that she could have developed ulceration, scarring of the cornea and eventually blindness.

The next stop was to be the tiny village of Remanso, falling on the river bordering Brazil. Although the village once had an airport, the arrival of electricity a few years ago meant wires across the landing strip that made it unusable and “the jungle had taken it back!” They flew instead to a naval base around 10 km away and faced some interrogation on arrival. They then travelled to the village on an outboard motored boat. Although David had identified 35 potential patients from the nearby areas, only 5 turned up – possibly because the journey of several kilometres was too difficult or costly, or perhaps because of a distrust of “gringos”.

The scenery and wildlife they saw while there was “exquisite” – birds such as heron, fish, and even amphibious capybaras. But Remanso was far poorer that Baures. Mosquitoes remained bothersome; despite sleeping under a net Romain got plenty of bites.

The place certainly had its charm, but it was a huge challenge to carry out ophthalmic work. Although the clinic was nice, there were a range of difficulties – such as red-brown water coming out of taps and, this time, no A/C. According to Romain “it was like working in a sauna”, with hands slipping around inside rubber gloves! (Since then a lady had donated an A/C unit). Romain was pleased to be able to help the patients – several of whom gave mango and sweet potatoes by way of thanks.

A lack of local ophthalmologists in Remanso meant there was no-one to really impart skills to; yet they have helped elsewhere and AMM plans more missions with the ambition of spreading skills to remote rural areas. AMM also want to use donations from their supporters to improve infrastructure and enhance the education and training of local health workers.

Romain ended his exhilarating, picture-filled talk by thanking us for our support.

To find out more about the Andean Medical Mission click here.

Picture: Romain De Cock talking to members about eye surgery in Bolivia. Picture credit: Rotary Club of Canterbury.